Aaron Beck was one of the first people to say that the way people think about things can cause symptoms of mental illness. In fact, the way people think about and process personal information can maintain this depressive state.

In particular, Beck’s (1979) cognitive theory says that the cognitive triad is a key process that makes depressive symptoms worse. Often, depression seems like it will never end because of these patterns of thinking.

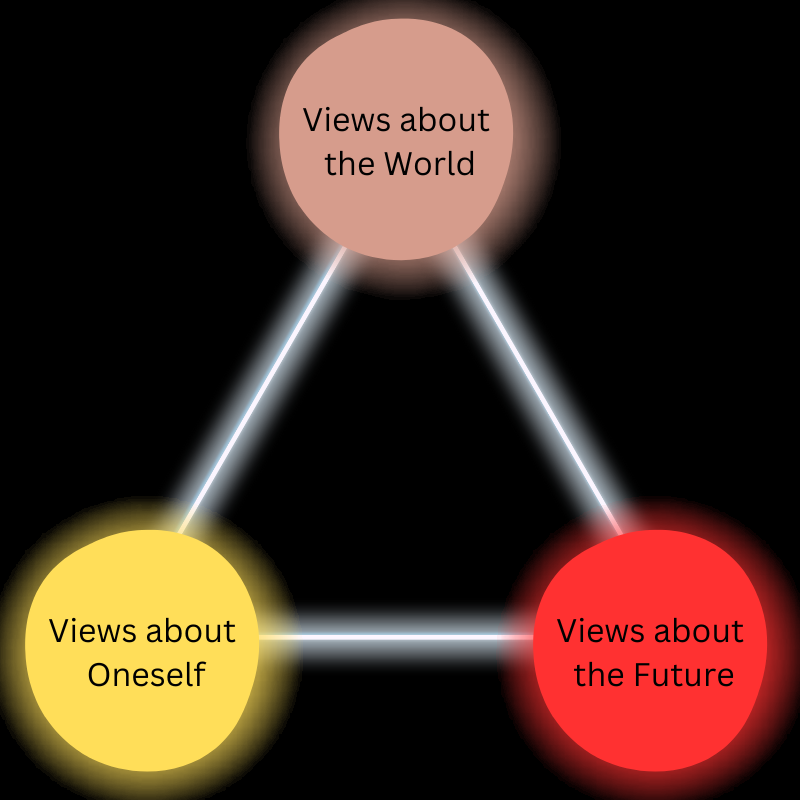

This concept is a three-part system made up of bad views of the self, the world, and the future.

In this article, I will attempt to describe the cognitive triad using both negative and positive views.

Structure of the Cognitive Triad

One of Beck’s most important ideas is that cognitive mental illness is caused by three categories of maladaptive views about one’s circumstances.

These three categories are shown below:

Negative thoughts of the self-might affect one’s self-worth. Negative views of the world might make people paranoid. Or it could be that they think that the world and/or other people are unfair. Having a negative view of the future means thinking that it will be hard and that the problems you are having now will last forever.

On the other hand, some thoughts are more positive. These could be about the self, e.g I’m enjoying myself; I feel good; I am a part of something that’s meaningful. Or it could be about the world. For example, the world is interesting, nature is beautiful, humans are good. Positive thoughts do not however mean morally or realistically better. Hence, the positive cognitive triad has moral limitations, much like the negative cognitive triad. However, it can also make people happier, more satisfied with their life, and less likely to become depressed.

To put it another way, resilience helps people think positively. They have a positive view about themselves, the world, and the future. This in turn improves their health and makes them feel less stressed.

Views About Oneself

Negative

A bad view of the self is a trait of many illnesses and feelings. These conditions are obviously not healthy, such as depression or anxiety. Some of these feelings could include boredom or maladaptive daydreaming – these negative emotions might not be full blown disorders.

People who are negative could think they are flawed, inadequate, and unworthy. Tarlow and Haaga (1996) confirmed a link between having a bad view of oneself and having negative feelings in general. This backs up what the older and newer literature indicates.

People with more frequent negative states tend to have more negative views of themselves.

Positive

It is said that resilient people are self-efficacious, bold, and driven (Wagnild & Young, 1990). People with these traits are more likely to talk positively to themselves. So, this improves their self-image and makes them more independent. People who are strong have a good attitude about themselves. This attitude makes them look for and enjoy situations that make them feel good about themselves (Walsh & Banaji, 1997). In turn, they improve their mental health.

Views About the World

Negative

When someone is feeling down, they start to see the world in a bad light. For instance, people who are sad are unhappy with their current life and think that everyone is expecting too much from them. This indicates that they view the world having too many hardships. Moreover, they could perceive themselves as inferior to many people in their surroundings. This connects views about the self to the view of the world as well.

Positive

Conversely, a positive view of the world is common among people who are highly resilient (Parr et al., 1998). These people want to get back on their feet after problems and move on. People who have a positive view of the world are better able to see chances in tough situations and come up with ways to solve problems (Wang, 2009).

So, being able to think straight during tough circumstances makes them less prone to depression.

Views About the Future

Negative

People who have major mental problems might not be optimistic about the future. When someone is sad, they do not usually believe they can achieve their goals. According to a study by Leondari et al. (1998), these ideas about the future self might make it harder for students to do well in school.

However, having views of the future that are too positive could be a major issue as well.

Positive

Research shows that people who are strong are sure in their ability to see the future (Klohnen, 1996). For example, Zaleski et al. (1998) found that college students with a lot of hope are less affected by the bad effects of worry and have fewer health problems as a result. Moreover, they are likely to accept self-agentic talk, such as “I can do this” and “I am not going to be stopped” (Snyder et al., 1998).

According to past studies, people who have a lot of hope are better at fixing problems. Mak et al. (2011) say that they are more likely to take on tasks and use active coping techniques instead of passive-avoidant ones. Because of this, they are more likely to keep going when things get tough or stressful.

Having said this, there are issues with viewing the future too positively as well. For instance, Maden et al. (2016) found that employees who had higher positive evaluations of their future were less satisfied than those who had less positive views.

This could show how having unrealistic positive expectations of the world could negatively impact us.

Final Evaluation

Even though it is very important, it is still not clear what the theory and empirical state of the cognitive triad is. On the one hand, many theories say there is only one dimension. In other words, the triad’s three parts don’t really exist as three separate things; they combine. So, the cognitive triangle describes how people think about the self and two specific parts of the self: the future and the world (McIntosh & Fischer, 2000).

Beck (1979) acknowledged this quandary. However, he said that despite this correlation, the cognitive triad is still useful for clinical work. This is similar to what Albert Ellis said regarding thinking in ‘musts’ – that certain things must happen.

Some studies found that negative views of the self and the future were most strongly linked to depressive symptoms in teens (Braet et al., 2015; Timbremont & Braet, 2006). Other studies also looked at the role of negative views of the world in kids and teens (Epkins, 2000; Jacobs & Joseph, 1997).

There is one broad consensus: our beliefs significantly affect our experience.

This is one of the core curative processes in psychotherapy.

References

- Beck, A. T. (1979). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. Penguin.

- Braet, C., Wante, L., Van Beveren, M. L., & Theuwis, L. (2015). Is the cognitive triad a clear marker of depressive symptoms in youngsters?. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 24, 1261-1268.

- Epkins, C. C. (2000). Cognitive specificity in internalizing and externalizing problems in community and clinic-referred children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29(2), 199-208.

- Haaga, D. A., Dyck, M. J., & Ernst, D. (1991). Empirical status of cognitive theory of depression. Psychological bulletin, 110(2), 215.

- Jacobs, L., & Joseph, S. (1997). Cognitive Triad Inventory and its association with symptoms of depression and anxiety in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 22(5), 769-770.

- Klohnen, E. C. (1996). Conceptual analysis and measurement of the construct of ego-resiliency. Journal of personality and social psychology, 70(5), 1067.

- Leondari, A., Syngollitou, E., & Kiosseoglou, G. (1998). Academic achievement, motivation and future selves. Educational studies, 24(2), 153-163.

- Maden, C., Ozcelik, H., & Karacay, G. (2016). Exploring employees’ responses to unmet job expectations: The moderating role of future job expectations and efficacy beliefs. Personnel Review, 45(1), 4-28.

- McIntosh, C. N., & Fischer, D. G. (2000). Beck’s cognitive triad: One versus three factors. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 32(3), 153.

- Parr, G. D., Montgomery, M., & DeBell, C. (1998). Flow theory as a model for enhancing student resilience. Professional School Counseling, 1(5), 26-31.

- Snyder, C. R., LaPointe, A. B., Jeffrey Crowson, J., & Early, S. (1998). Preferences of high-and low-hope people for self-referential input. Cognition & Emotion, 12(6), 807-823.

- Tarlow, E. M., & Haaga, D. A. (1996). Negative self-concept: Specificity to depressive symptoms and relation to positive and negative affectivity. Journal of Research in Personality, 30(1), 120-127.

- Timbremont, B., & Braet, C. (2006). Brief report: A longitudinal investigation of the relation between a negative cognitive triad and depressive symptoms in youth. Journal of Adolescence, 29(3), 453-458.

- Wagnild, G., & Young, H. M. (1990). Resilience among older women. Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 22(4), 252-255.

- Walsh, W. A., & Banaji, M. R. (1997). The Collective Self a. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 818(1), 193-214.

- Wang, J. (2009). A study of resiliency characteristics in the adjustment of international graduate students at American universities. Journal of Studies in International Education, 13(1), 22-45.

- Zaleski, E. H., Levey-Thors, C., & Schiaffino, K. M. (1998). Coping mechanisms, stress, social support, and health problems in college students. Applied Developmental Science, 2(3), 127-137.

I am a Clinical Psychologist and a Lecturer of Psychology at Government College, Renala Khurd. Currently, I teach undergraduate students in the morning and practice psychotherapy later in the day. On the side, I conjointly run Psychologus and write regularly on topics related to psychology, business and philosophy. I enjoy practicing and provide consultation for mental disorders, organizational problems, social issues and marketing strategies.