Written by Najwa Bashir

Dyscalculia

Two of the most common learning disorders are dyslexia and dysgraphia. One is dyscalculia, characterized by having trouble with math (Ahuja et al., 2021). Dyscalculia is a learning disorder that makes it hard to understand and use numbers. This can affect students’ mathematics education and well-being (Asalisa & Meiliasari, 2023). According to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), dyscalculia is a unique developmental disease that causes problems with speech, motor skills, and the ability to see and understand where things are in space (Aquil, 2020). Although dyscalculia is as prevalent as dyslexia and dysgraphia, it is less well-known and has received less research attention than the other two (Grigore, 2020). Consequently, many educators possess an inadequate understanding of dyscalculia (Kunwar & Sharma, 2020), and pupils afflicted with dyscalculia fail to receive the necessary assistance during their mathematical education (Salisa & Meiliasari, 2023).

Prevalence

Dyscalculia affects 3-7% of all children, adolescents, and adults. Severe, ongoing difficulties with math computations cause significant impairment in the workplace, in school, and daily life. It also increases the likelihood of co-occurring mental problems (Haberstroh & Schulte-Körne, 2019).

According to large-scale cohort research conducted in England, there are significant psychological and economic problems linked to low mathematical proficiency: Of those impacted, 70–90% dropped out of school before the age of 16, and just a small percentage had full-time jobs when they were 30. Compared to people without dyscalculia, their chances of being jobless and experiencing depressed symptoms were twice as high (Parsons & Bynner, 2005). An estimated £2.4 billion is spent annually in Great Britain on expenses related to severe mathematical impairment (Gross, 2006).

Diagnostic Criteria for Dyscalculia

Behavioral specialists can determine whether an individual has dyscalculia or a severe arithmetic problem by using the Dutch protocol “Dyscalculia: Diagnostics for Behavioural Professionals” (DDBP). The following criteria are addressed by the DDBP procedure in order to diagnose dyscalculia:

- First criterion: To ascertain whether the math issue exists and how serious it is

- Second criterion: To identify the math issue associated with the individual’s capabilities

- Third criterion: Assessing the mathematical problem’s obstinacy

The protocol also notes that a fourth criterion—difficulties that predate the age of seven—is incorporated in many studies. For most kids, this is accurate; nevertheless, dyscalculia is typically identified later in life among (very) brilliant kids.

Diagnostic Features of Dyscalculia

The following are the typical features of dyscalculia (Salisa & Meiliasari, 2023):

Trouble understanding and using numbers and amounts starting in preschool

- It’s hard to make the connection between a number (like 2) and the thing it stands for (like 2 apples).

- People don’t fully understand the relationship between numbers and amounts (two apples and one apple = 2 + 1).

- Because of this, it’s hard to count, compare two numbers or amounts, quickly evaluate and name small groups of dots, find a number’s position on the number line, understand the place-value system, and transcode.

Problems with simple math operations and other math-related tasks

- Individuals don’t understand how to use computation rules because they don’t understand numbers and amounts well enough (17 + 14 = 1 + 1 and 7 + 4 = 13 or 211).

- Questions with remembering math facts (like the multiplication table), which are facts that let you get the answers to simple math questions without having to do the math all over again.

- No change from counting to non-counting methods (8 + 4 = 8 + 2 and 2 = 12) when doing math (8 + 4 = 9, 10, 11, 12 = 12).

- These problems get worse as the math gets harder (bigger number range, written calculations, computations with multiple steps, word problems).

Important

- Finger-counting is not a sign of dyscalculia; it is a normal way to help you remember math facts and learn how to do calculations quickly and correctly. Finger-counting over and over, especially for simple calculations that are done over and over, does show that there is a problem with the calculations.

- What matters is not just that there are mistakes in the calculations; what matters is their range, how long they last, and how often they happen.

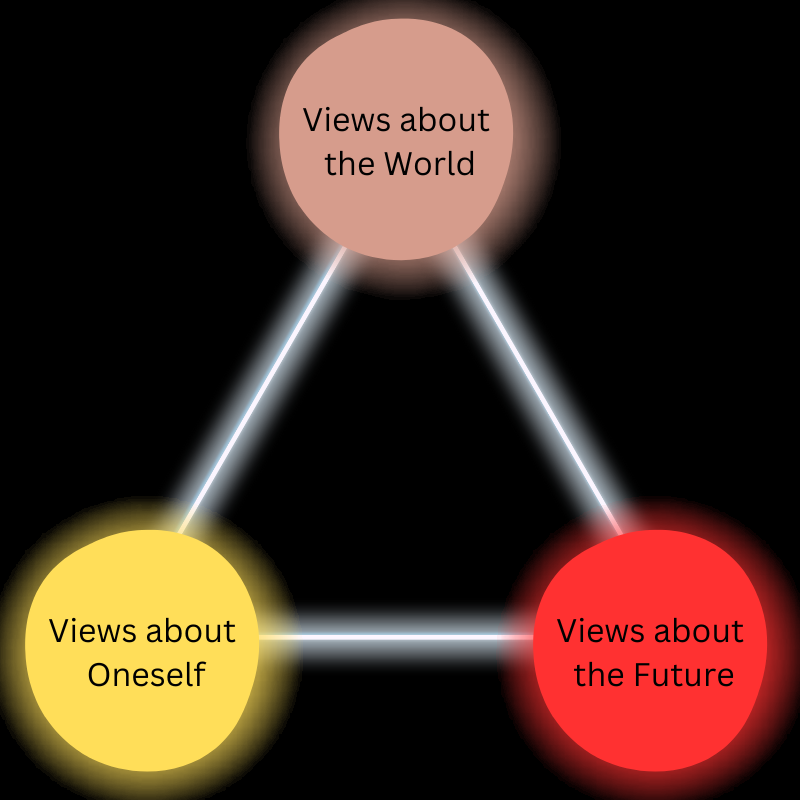

The main thing that is used to diagnose dyscalculia is a difference between a person’s brain and their supposed math skills. In a full test that can also be used to plan a therapy intervention, the cause of dyscalculia and problems understanding visual information should both be taken into account. This should be taken into account when choosing the right test methods. The new definition of dyscalculia takes into account not only IQ and math success in school, but also problems with basic skills that are common in people with dyscalculia. The IQ difference and the best IQ test for dyscalculia are still debated. One new thing about this work is that it uses a multidisciplinary method to give a full picture of dyscalculia and how to diagnose it. This could help scholars from other fields (Aquil, 2020).

Early diagnosis of dyscalculia will ensure early management of the problem. The aforementioned criteria and diagnostic features can help diagnose dyscalculia.

References

- Ahuja, N. J., Thapliyal, M., Bisht, A., Stephan, T., Kannan, R., Al-Rakhami, M. S., & Mahmud, M. (2021). An investigative study on the effects of pedagogical agents on intrinsic, extraneous and germane cognitive load: experimental findings with dyscalculia and non-dyscalculia learners. IEEE Access, 10, 3904-3922. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3115409

- Aquil, M. A. I. (2020). Diagnosis of dyscalculia: A comprehensive overview. South Asian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 1(1), 43-59. Available at: https://acspublisher.com/journals/index.php/sajssh/article/view/1124

- Grigore, M. (2020). Towards a standard diagnostic tool for dyscalculia in school children. CORE Proceedings, 1(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21428/bfdb1df5.d4be3454

- Gross, J. (2006). The long term costs of literacy difficulties. KPMG Foundation.

- Haberstroh, S., & Schulte-Körne, G. (2019). The diagnosis and treatment of dyscalculia. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 116(7), 107. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2019.0107

- Kunwar, R., & Sharma, L. (2020). Exploring Teachers’ Knowledge and Students’ Status about Dyscalculia at Basic Level Students in Nepal. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 16(12). https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/8940

- Parsons, S., & Bynner, J. (2005). National Research and Development Centre for adult literacy and numeracy. London: Institute of Education.

- Salisa, R. D., & Meiliasari, M. (2023). A literature review on dyscalculia: What dyscalculia is, its characteristics, and difficulties students face in mathematics class. Alifmatika: Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pembelajaran Matematika, 5(1), 82-94. https://doi.org/10.35316/alifmatika.2023.v5i1.82-94

- Van Luit, J. E. (2019). Diagnostics of dyscalculia. International handbook of mathematical learning difficulties: From the laboratory to the classroom, 653-668. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97148-3_38